DUNOIR VALLEY – Mountains cradle the

Diamond G Ranch in northwest Wyoming. A long, dirt road winds from a

two-lane highway into the ranch where cows graze in the summer and elk

wander during the winter. A two-story barn towers over stables and

a few nearby houses. It feels safe, protected by the snowcapped

mountains that stand guard in the distance.

But over those peaks almost 20 years ago came a threat Jon and Debbie Robinett couldn’t prepare for.

About a year after gray wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, they arrived at the ranch. The great canines sowed destruction, killing 61 calves in a herd of 800. Sometimes the carcasses were found in mangled pieces. Other times they simply disappeared.

Jon keeps envelopes of photos to document the carnage. One day in November, standing in his kitchen wearing a white and tan button-down shirt tucked into dark blue Wranglers, he flipped through the pictures. One shows a horse that had been dead for 36 hours. Another is a calf taken down 200 yards from the house. “This is a yearling heifer the wolves killed. A sow and cubs came down to eat it and the wolves killed the cubs,” said Jon.

In two decades, the Robinetts have lost hundreds of cows and calves, five horses, seven dogs and an 11-day-old painted colt to wolves. “We learned real early on to start documenting, taking pictures,” said Debbie. “Sometimes it’s really hard to do, like with my dogs, to take pictures of dead dogs. But you had to do it, if you didn’t have the proof, it didn’t work.”

But mixed in that stack of pictures, and on Debbie’s computer where she keeps digital images, are thousands of photos of wolves themselves. The couple describes them with equal emotion. “This was Paul, caught in a trap,” Jon said, looking at a picture of a black wolf he’d named. “We caught him when he was a pup in August. He weighed 42 pounds and we caught him again in November and he weighed 90 pounds.”

“We used to go out and count the pups -- well, we still do -- to see how many pups they have. There are five here. They’re real unique animals, even at a young age.” The Robinetts' relationship with wolves in some ways encapsulates the journey followed by Wyoming’s ranchers, conservationists, hunters, politicians and recreationists in the last 20 years.

Those relationships have, at times, been filled with frustration, anger, sadness and awe. Jon was involved in one of the first lawsuits filed against the federal government after wolves were reintroduced. Debbie bought wolf hunting licenses. But they also spend hours roaming the mountains, hoping to catch glimpses of the large canines.

Some of the raw emotion associated with the animals following their reintroduction has abated in recent years, though bumper stickers calling wolves government-sponsored terrorists or telling people to shoot, shovel and shut up are not uncommon. Wolf management meetings that once drew hundreds now may bring only a handful.

Jon wanted to work with the carnivores from the beginning. He believed that humans and wolves could coexist. Some early wolf opponents are beginning to find a middle ground, too.

One drainage over from the Robinetts, fellow Dubois-area rancher Reg Phillips is building a similar tolerance for the hungry carnivores as long as wolves are managed and ranchers are paid for livestock kills. “I like wildlife, I love looking at big elk and deer, and I like seeing grizzlies,” Phillips said. “Wolves, they’re big and neat. But they’re also big and meat eaters. If they would manage wolves, I’d be able to accept a little larceny, a little death loss.”

*****

No one has a firm count of how many wolves once roamed Wyoming’s mountains and plains, but between 1893 and 1927 alone, hunters killed more than 36,160 wolves in the Cowboy State, according to a 1954 issue of Wyoming Wildlife magazine.

In late May, 1943, a sheepherder on the Wind River Indian Reservation shot the last known one in Wyoming. By the mid-'50s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared Wyoming free of wolves.

Grizzly bears followed a similar trajectory, with only a few dozen left deep within Yellowstone.

That meant an entire generation of ranchers in northwest Wyoming never dealt with grazing cattle and sheep alongside big predators.

Jon and Debbie aren't strangers to ranching in the West. Jon’s great-grandfather settled outside of Casper in the late 1800s. Debbie’s parents came to Casper in the late 1940s. Jon remembers stories from old-timers of living and working with wolves, carnivores long gone by the time younger generations took over.

He and Debbie met in the fifth grade and married out of high school. They managed ranches across Wyoming and Texas before becoming managers of the Diamond G Ranch outside of Dubois in 1989.

A few years after wolves started moving onto the ranch, the owner was ready to sue. “There is a time and a place for everything. This might not be the right place,” Jon said. “Most ranchers approached it that they lose X amount of cows, and then you lose another 5 to 6 percent to wolves, they’re trying to make a living and this is an unnecessary loss.”

Many of his ranching neighbors outside of Dubois and in other parts of the northwest corner felt similarly. To allay the fears and offset wolf kills, Defenders of Wildlife, a national wildlife advocacy group, initially established a payment fund for wolf kills to cattle and sheep. The state later took over payments.

Each rancher with a confirmed cow, calf or bull killed by wolves would receive seven times the value of the animal to account for others likely killed and not found. It helped keep ranches alive, but it didn’t heal the wounds. “We’re not in the business to feed big predators, we’re in the business to feed people,” said Albert Sommers, a rancher near Pinedale. “It’s not always clean kills, and they don’t always pick out the sick and weak.”

And proving kills in order to be reimbursed turned out to be even harder. Grizzly bears tended to take cows and calves down and eat them right there; a kill looks like the animal was skinned out. Wolves would bite at their bellies and other soft tissue with teeth dulled from years of chewing. A dead cow would sometimes look from the outside like it keeled over of natural causes, Jon said, but would be pulverized on the inside. “Fish and Wildlife didn’t know. They hadn’t dealt with wolves before,” he said. “They thought maybe we had a sick one and it died and they ate it.”

Debbie would spend days and weeks nursing animals found alive back to health, hosing down wounds, rubbing ointment in cuts, bracing legs. The cow and calf losses hurt, but it was their pets that really angered her.

A few years after the reintroduction, Debbie left the house around 10 p.m. to lock Booger, her dog, in the horse barn. About 200 yards separated her house and the outbuilding. She used a spotlight to look for wolves and didn’t see any. The two walked about 30 yards in the dark, the dog about 10 feet in front of Debbie, when a pack of wolves attacked the dog.

Debbie wheeled around and ran to the house. She jumped in her Jeep and flashed her headlights on the wolves. “It must have broken it up or my screaming did, I don’t know what,” she said. She couldn’t find Booger until the next day. He was still alive. “He was bit up from one end of his body to the other,” she said. “We shaved him. He was a mess.”

Territorial to a fault, wolves will kill any canine in their area, Jon said. What the couple also learned is that humans are rarely in danger. Even that close, the wolves didn’t want to attack Debbie -- they wanted the other canine.

Either way, Debbie lost patience with them. “I like to take pictures of them. I do like to do that, because they’re unique,” she said. “But they’ve impacted my life and killed my dog and my horses, and I’m sorry, the wolves are going to have to pay for that.” But the Robinetts also knew wolves weren’t likely going anywhere. And if they were there to stay, Jon figured he would find a way to work with them.

*****

It may sound counterintuitive, but cows, Jon said, can learn how to scare away a pack of wolves.

“We were sitting here one day, and there were 200 cows in that pasture,” he said, standing by an electric fence surrounding pasture in the DuNoir Valley. “Seven wolves came in there, and not one or two cows, but all 200 of them chased them through the fence. The wolves were looking at them like that wasn’t supposed to happen.”

When the cows couldn’t defend themselves, Jon and Debbie would figure out how. One night during calving season, Jon grated the dirt road leading to his pasture and the next morning found wolf tracks where the pack crossed from the mountains into his cattle.

The next night, he sat there with a spotlight. When the wolves came down, he and Debbie hollered at them and flashed their lights. The wolves hightailed it for the woods. They wouldn’t stay away forever. Each night the couple repeated the practice, but they also didn’t lose any cows or calves while they were locked in the pasture.

Defenders of Wildlife preaches a similar kind of non-lethal defense with sheep. They’ve had successes in Idaho and hope to help more ranchers use the methods, said Suzanne Stone, Northern Rockies representative for Defenders of Wildlife. “The national mandate is to help create coexistence between wildlife and people,” Stone said. “Wolves can’t coexist if they’re dead.”

Jon said it takes long days and even longer nights to figure out how to keep wolves away from cattle, but it is possible. “We lost 61 calves that first year. The next year we lost 56, the next 53,” he said. “The longer the cattle were exposed to predation, the fewer we lost. This year we had one wolf kill, one bear kill and two missing calves.” The wolves seem to feed mostly on elk now.

Both Jon and Reg Phillips, his neighbor, want to see wolves taken off the endangered species list. They were removed in 2008, then placed back on, then removed in 2012 and placed back on again in September over concerns about Wyoming’s management plan. Wyoming’s congressional delegation hopes pass a law similar to Montana and Idaho that would permanently delist wolves. Right now, anything could happen.

Both Jon and Phillips recognize not all ranchers have had similar experiences with wolves. Some have lost more animals, some fewer. Some aren’t nearly as tolerant. But ultimately, wolves are here to stay. People should try and work with them. “It’s not the wolves’ fault they’re here. They didn’t ask to be loaded up and brought down here,” Jon said. “Wolves are wolves. They haven’t changed what they’ve done for a lot of years.”

But over those peaks almost 20 years ago came a threat Jon and Debbie Robinett couldn’t prepare for.

About a year after gray wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, they arrived at the ranch. The great canines sowed destruction, killing 61 calves in a herd of 800. Sometimes the carcasses were found in mangled pieces. Other times they simply disappeared.

Jon keeps envelopes of photos to document the carnage. One day in November, standing in his kitchen wearing a white and tan button-down shirt tucked into dark blue Wranglers, he flipped through the pictures. One shows a horse that had been dead for 36 hours. Another is a calf taken down 200 yards from the house. “This is a yearling heifer the wolves killed. A sow and cubs came down to eat it and the wolves killed the cubs,” said Jon.

The

last rays of sunlight touch the snowy peak of Coffin Butte on Thursday,

Nov. 20, 2014, at the head of the Dunoir Valley outside Dubois. The

valley, bordering the Washakie Wilderness and roughly 70 miles from

Yellowstone National Park, is home to the Diamond G Ranch, a cattle

operation that has been forced to adapt to increasing predation since

the reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone in 1995. (Ryan Dorgan,

Star-Tribune)

In two decades, the Robinetts have lost hundreds of cows and calves, five horses, seven dogs and an 11-day-old painted colt to wolves. “We learned real early on to start documenting, taking pictures,” said Debbie. “Sometimes it’s really hard to do, like with my dogs, to take pictures of dead dogs. But you had to do it, if you didn’t have the proof, it didn’t work.”

But mixed in that stack of pictures, and on Debbie’s computer where she keeps digital images, are thousands of photos of wolves themselves. The couple describes them with equal emotion. “This was Paul, caught in a trap,” Jon said, looking at a picture of a black wolf he’d named. “We caught him when he was a pup in August. He weighed 42 pounds and we caught him again in November and he weighed 90 pounds.”

“We used to go out and count the pups -- well, we still do -- to see how many pups they have. There are five here. They’re real unique animals, even at a young age.” The Robinetts' relationship with wolves in some ways encapsulates the journey followed by Wyoming’s ranchers, conservationists, hunters, politicians and recreationists in the last 20 years.

Those relationships have, at times, been filled with frustration, anger, sadness and awe. Jon was involved in one of the first lawsuits filed against the federal government after wolves were reintroduced. Debbie bought wolf hunting licenses. But they also spend hours roaming the mountains, hoping to catch glimpses of the large canines.

Some of the raw emotion associated with the animals following their reintroduction has abated in recent years, though bumper stickers calling wolves government-sponsored terrorists or telling people to shoot, shovel and shut up are not uncommon. Wolf management meetings that once drew hundreds now may bring only a handful.

15M,

or "Carter's Hope," was the first Canadian wolf captured for

reintroduction into Yellowstone National Park. He became alpha male of

the Washakie Pack, and along with his mate, was the first to den outside

Yellowstone following reintroduction. Carter's Hope raised five pups

before being killed Oct. 26, 1997, for preying on livestock on the

Diamond G Ranch in the Dunoir Valley, and is now mounted at the Shoshone

National Forest Wind River Ranger District office outside Dubois. (Ryan

Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

Jon wanted to work with the carnivores from the beginning. He believed that humans and wolves could coexist. Some early wolf opponents are beginning to find a middle ground, too.

One drainage over from the Robinetts, fellow Dubois-area rancher Reg Phillips is building a similar tolerance for the hungry carnivores as long as wolves are managed and ranchers are paid for livestock kills. “I like wildlife, I love looking at big elk and deer, and I like seeing grizzlies,” Phillips said. “Wolves, they’re big and neat. But they’re also big and meat eaters. If they would manage wolves, I’d be able to accept a little larceny, a little death loss.”

*****

No one has a firm count of how many wolves once roamed Wyoming’s mountains and plains, but between 1893 and 1927 alone, hunters killed more than 36,160 wolves in the Cowboy State, according to a 1954 issue of Wyoming Wildlife magazine.

In late May, 1943, a sheepherder on the Wind River Indian Reservation shot the last known one in Wyoming. By the mid-'50s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared Wyoming free of wolves.

Grizzly bears followed a similar trajectory, with only a few dozen left deep within Yellowstone.

That meant an entire generation of ranchers in northwest Wyoming never dealt with grazing cattle and sheep alongside big predators.

Jon and Debbie aren't strangers to ranching in the West. Jon’s great-grandfather settled outside of Casper in the late 1800s. Debbie’s parents came to Casper in the late 1940s. Jon remembers stories from old-timers of living and working with wolves, carnivores long gone by the time younger generations took over.

Rancher

Jon Robinett looks north toward the Washakie Wilderness while preparing

to check trail cameras for wolves on Thursday, Nov. 20, 2014, on the

Diamond G Ranch outside Dubois. "It's not the wolves' fault they're

here. They didn't ask to be loaded up and brought down here," Robinett

said. "Wolves are wolves. They haven't changed what they've done for a

lot of years." (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

He and Debbie met in the fifth grade and married out of high school. They managed ranches across Wyoming and Texas before becoming managers of the Diamond G Ranch outside of Dubois in 1989.

A few years after wolves started moving onto the ranch, the owner was ready to sue. “There is a time and a place for everything. This might not be the right place,” Jon said. “Most ranchers approached it that they lose X amount of cows, and then you lose another 5 to 6 percent to wolves, they’re trying to make a living and this is an unnecessary loss.”

Many of his ranching neighbors outside of Dubois and in other parts of the northwest corner felt similarly. To allay the fears and offset wolf kills, Defenders of Wildlife, a national wildlife advocacy group, initially established a payment fund for wolf kills to cattle and sheep. The state later took over payments.

Each rancher with a confirmed cow, calf or bull killed by wolves would receive seven times the value of the animal to account for others likely killed and not found. It helped keep ranches alive, but it didn’t heal the wounds. “We’re not in the business to feed big predators, we’re in the business to feed people,” said Albert Sommers, a rancher near Pinedale. “It’s not always clean kills, and they don’t always pick out the sick and weak.”

One

drainage east of the Dunoir Valley, cattle winter Friday, Nov. 21,

2014, at the Rocking Chair Ranch near Dubois. Reg Phillips manages the

ranch's Diamond D Cattle Company, which runs cattle on 71,000 acres of

deeded and public land in prime wolf and grizzly bear range above

Dubois. "There for a couple of years, it was just a nightmare around

here," he said. (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

And proving kills in order to be reimbursed turned out to be even harder. Grizzly bears tended to take cows and calves down and eat them right there; a kill looks like the animal was skinned out. Wolves would bite at their bellies and other soft tissue with teeth dulled from years of chewing. A dead cow would sometimes look from the outside like it keeled over of natural causes, Jon said, but would be pulverized on the inside. “Fish and Wildlife didn’t know. They hadn’t dealt with wolves before,” he said. “They thought maybe we had a sick one and it died and they ate it.”

Debbie would spend days and weeks nursing animals found alive back to health, hosing down wounds, rubbing ointment in cuts, bracing legs. The cow and calf losses hurt, but it was their pets that really angered her.

A few years after the reintroduction, Debbie left the house around 10 p.m. to lock Booger, her dog, in the horse barn. About 200 yards separated her house and the outbuilding. She used a spotlight to look for wolves and didn’t see any. The two walked about 30 yards in the dark, the dog about 10 feet in front of Debbie, when a pack of wolves attacked the dog.

Debbie wheeled around and ran to the house. She jumped in her Jeep and flashed her headlights on the wolves. “It must have broken it up or my screaming did, I don’t know what,” she said. She couldn’t find Booger until the next day. He was still alive. “He was bit up from one end of his body to the other,” she said. “We shaved him. He was a mess.”

Territorial to a fault, wolves will kill any canine in their area, Jon said. What the couple also learned is that humans are rarely in danger. Even that close, the wolves didn’t want to attack Debbie -- they wanted the other canine.

A

wolf crossing sign hangs beside a gate leading to the Diamond G Ranch

in the Dunoir Valley outside Dubois. In the years following the 1995

reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park, the valley -

some 70 miles from the park - was a hotbed for wolf predation on the

ranch's cattle herd. (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

Either way, Debbie lost patience with them. “I like to take pictures of them. I do like to do that, because they’re unique,” she said. “But they’ve impacted my life and killed my dog and my horses, and I’m sorry, the wolves are going to have to pay for that.” But the Robinetts also knew wolves weren’t likely going anywhere. And if they were there to stay, Jon figured he would find a way to work with them.

*****

It may sound counterintuitive, but cows, Jon said, can learn how to scare away a pack of wolves.

“We were sitting here one day, and there were 200 cows in that pasture,” he said, standing by an electric fence surrounding pasture in the DuNoir Valley. “Seven wolves came in there, and not one or two cows, but all 200 of them chased them through the fence. The wolves were looking at them like that wasn’t supposed to happen.”

When the cows couldn’t defend themselves, Jon and Debbie would figure out how. One night during calving season, Jon grated the dirt road leading to his pasture and the next morning found wolf tracks where the pack crossed from the mountains into his cattle.

The next night, he sat there with a spotlight. When the wolves came down, he and Debbie hollered at them and flashed their lights. The wolves hightailed it for the woods. They wouldn’t stay away forever. Each night the couple repeated the practice, but they also didn’t lose any cows or calves while they were locked in the pasture.

Defenders of Wildlife preaches a similar kind of non-lethal defense with sheep. They’ve had successes in Idaho and hope to help more ranchers use the methods, said Suzanne Stone, Northern Rockies representative for Defenders of Wildlife. “The national mandate is to help create coexistence between wildlife and people,” Stone said. “Wolves can’t coexist if they’re dead.”

Jon said it takes long days and even longer nights to figure out how to keep wolves away from cattle, but it is possible. “We lost 61 calves that first year. The next year we lost 56, the next 53,” he said. “The longer the cattle were exposed to predation, the fewer we lost. This year we had one wolf kill, one bear kill and two missing calves.” The wolves seem to feed mostly on elk now.

Jon

Robinett shuffles through photographs made to document the Diamond G

Ranch's livestock losses sustained by wolf predation on Wednesday, Nov.

19, 2014, in his home outside Dubois. Their two Great Pyrenees dogs were

two of seven that fell victim to wolves over two decades along with

hundreds of cows and calves, six horses, and an 11-day old pony. (Ryan

Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

Both Jon and Reg Phillips, his neighbor, want to see wolves taken off the endangered species list. They were removed in 2008, then placed back on, then removed in 2012 and placed back on again in September over concerns about Wyoming’s management plan. Wyoming’s congressional delegation hopes pass a law similar to Montana and Idaho that would permanently delist wolves. Right now, anything could happen.

Both Jon and Phillips recognize not all ranchers have had similar experiences with wolves. Some have lost more animals, some fewer. Some aren’t nearly as tolerant. But ultimately, wolves are here to stay. People should try and work with them. “It’s not the wolves’ fault they’re here. They didn’t ask to be loaded up and brought down here,” Jon said. “Wolves are wolves. They haven’t changed what they’ve done for a lot of years.”

source

Following

a late-night episode years ago when wolves attacked the Robinett's dogs

on their way from the house to the barn, Debbie Robinett never makes

the trip without a 9mm pistol. (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

High

above the Dunoir Valley, Jon Robinett positions a camouflaged trail

camera along a route commonly used by wolves on Thursday, Nov. 20, 2014,

on the Diamond G Ranch outside Dubois. It's not uncommon for wolves to

meander across the meadows surrounding the ranch house or even bed down

outside the Robinett's bedroom window. "That's one of the reasons I'm

still at this location, is the wildlife," Robinett said. "How many

places can you see it and interact with it?" (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

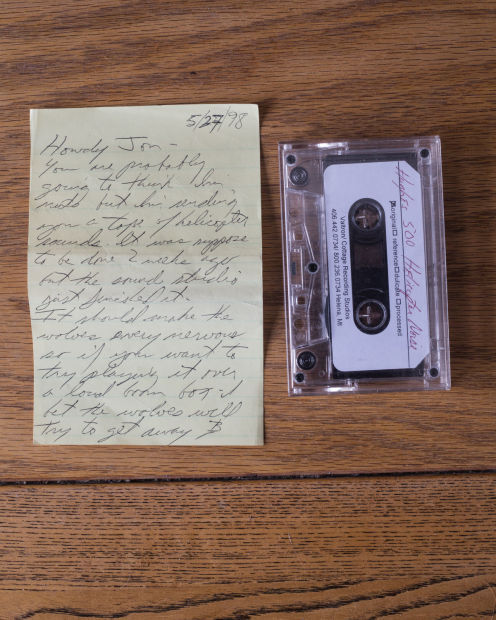

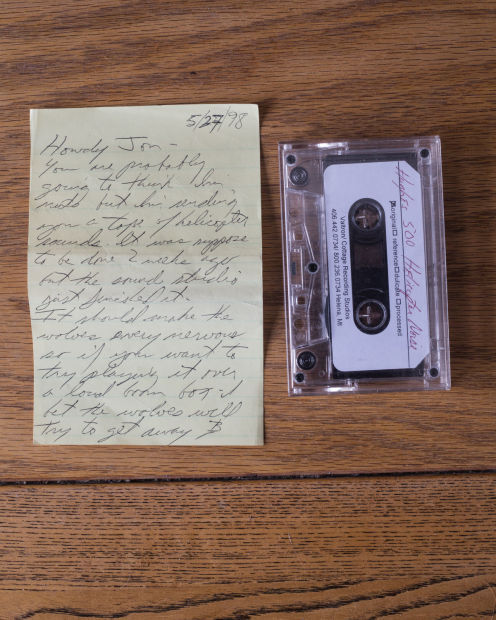

One

of the many non-lethal techniques the Robinetts tried to keep wolves at

bay came from Ed Bangs, then the Fish and Wildlife Service gray wolf

recovery coordinator. A letter from Bangs addressed to Jon Robinett

included a cassette tape labeled "Hughes 500 Helicopter Noise." Intended

to make the wolves nervous, the noise made them puzzled and curious

more than anything, Robinett said. (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)

Wolf

tracks lead into the Dunoir Valley from the high Sixmile drainage where

a nearby pack dens on Thursday, Nov. 20, 2014, on the Diamond G Ranch

outside Dubois. (Ryan Dorgan, Star-Tribune)