HELENA — A wandering wolf traveled nearly 700 miles through three states and one Canadian province before being shot and killed near Judith Gap last month for preying on sheep.

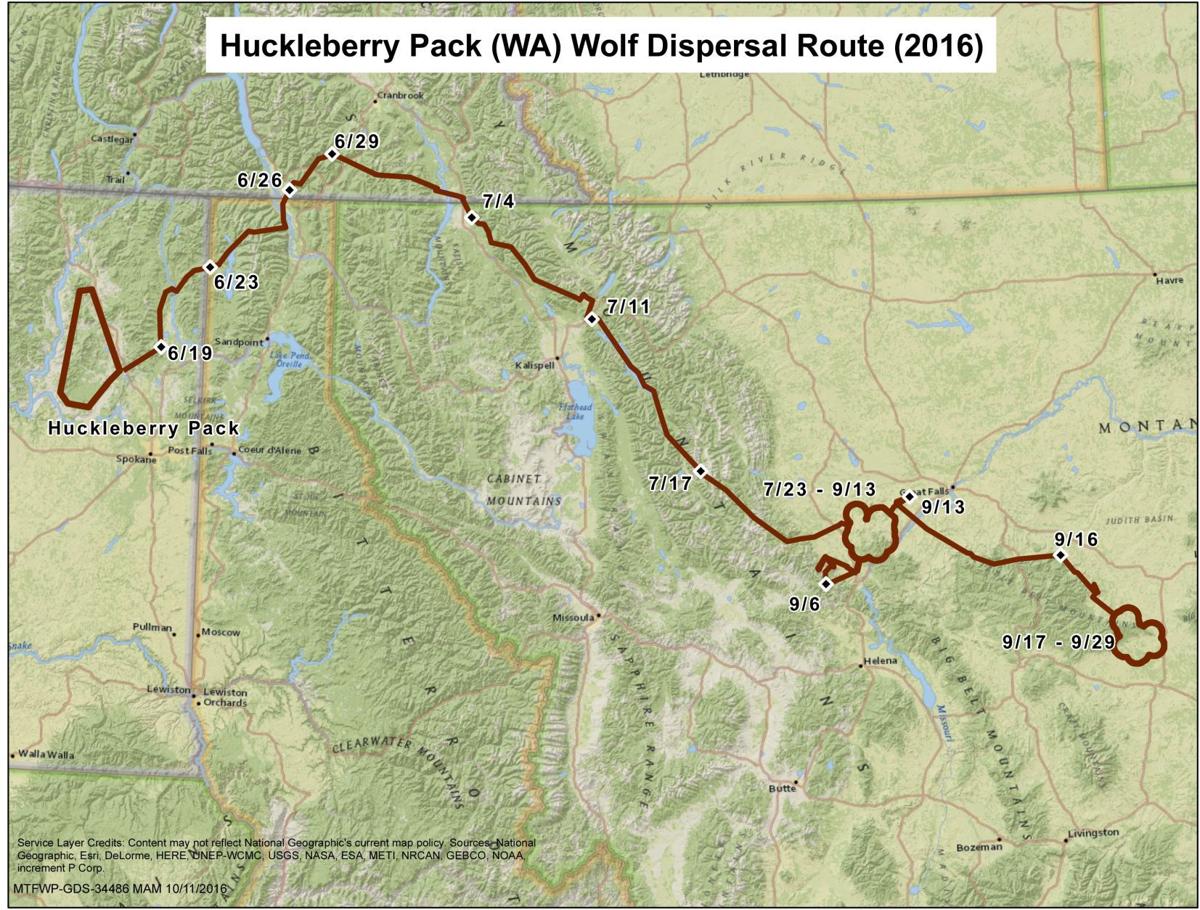

Washington Fish and Wildlife biologists collared the 2-year-old male wolf in February north of Spokane. Last June they tracked the animal as it left the Huckleberry Pack's territory, turning east into Idaho and north into Canada.

“Dispersal is a necessary and a very risky component of wolf population dynamics,” said Ty Smucker, wolf specialist with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. “As young wolves mature they typically disperse from their natal pack in search of potential mates and vacant territories in which to start their own packs.”

On the Fourth of July the wolf re-entered the United States near Eureka and headed southeast. In late July he emerged on the Rocky Mountain Front, staying in the area until September. Then he headed east, traveling west of Great Falls and north of the Little Belt Mountains.

“I was communicating with the biologist in Washington and we were keeping our fingers crossed that he’d keep out of trouble," Smucker said.

By Sept. 22 the wolf moved west of Judith Gap, when Wildlife Services received reports of predation on sheep. Federal officials confirmed the predation was by a wolf, and they shot the animal on Sept. 29 as it left a band of sheep it was reportedly preying on, Smucker said.

“He moved into an area where there were a lot of sheep, so unfortunately sooner or later he was probably going to kill one,” he added. “It was pretty obvious he was attacking sheep at night, and it doesn’t get a whole lot clearer than that when they saw him leaving the area.”

The wolf killed at least four sheep, and an additional 13 were bitten. Officials have not determined what ate two other sheep, he said.

Nonlethal methods were not tried, as predation began soon after the wolf’s arrival and no known wolf packs occupy the area.

Smucker explained that while wolves are managed by the state, federal officials have discretion under a memorandum of understanding to respond lethally to livestock losses. Part of that discretion comes with the remoteness of many predation incidents and related delays in response.

Marc Cooke, president of the Bitterroot Valley-based advocacy group Wolves of the Rockies, says he has concerns with the killing, particularly because the wolf was collared. He pointed out that Gov. Steve Bullock asked FWP to use education to avert killing collared wolves near national parks.

“If this guy from Wildlife Services sees a collar on a wolf, and even our own governor of Montana has encouraged (FWP) that if a wolf has a collar don’t kill it, then the directive should be nonlethal, not killing it,” he said.

Smucker said it was not clear whether the federal agent knew the wolf was collared.

Cooke also criticized the killing because wolf dispersal is important for genetic exchange.

“It’s a sad story that this wolf makes it through the killing fields of Idaho and then gets whacked in Montana,” he said. “This is a known wolf behavior, and how are we ever going to get a corridor down into Colorado up through the Yaak to improve genetic diversity if they’re so quick on the trigger?”

Jim Brown with the Montana Wool Growers Association noted Montana law dictates that lethal control is appropriate when predation occurs.

“This is an example where authorities came together and acted appropriately where a wolf has depredated on livestock,” he said. “Obviously the Montana Wool Growers supports that part of state law as a protection of private property. Lethal control is generally the last option taken when you have a species such as the wolf.”

Predator management works better with the support or tolerance of the agriculture industry, Brown contended, and allowing lethal measures when necessary builds that tolerance.

Regardless of debate over wildlife management, the wolf’s travels are “amazing” and shows the populations dispersing, he said.

As wolves increase in number and range across the Northern Rockies, Washington and Oregon, their propensity for long travels have generated headlines and fascinated wildlife enthusiasts.

In 2015 a wolf left its pack’s territory west of Missoula and ended up in British Columbia 600 miles away, according to FWP.

A wolf named OR7 was collared in Oregon in 2011 before a 1,000-mile journey into California and back to Oregon. The wolf continued to move back and forth between the states before establishing a pack in 2013, according to California Fish and Wildlife.

Montana’s wolf population has remained stable the past eight years with a minimum of more than 500.

No comments:

Post a Comment