Bill Stoller sits

with his wolf-hybrid dogs on Saturday, March 26, 2016, in Bisbee,

Arizona. (Photo by Courtney Pedroza/Special for Cronkite News)

SOUTHEAST ARIZONA — Inside a large chain-link cage at the Southwest Wildlife Conservation Center, a Mexican gray wolf gently moves from behind a tree and into the open air. It stands in the midday sun, dark-lined eyes looking intently beyond the fence, before settling under the tree for shade.

This is one of 16 wolves at the north Scottsdale center, part of the Mexican Wolf Species Survival Plan. The wolves in the enclosure are shy, dusty gray and brown coats disguising them against the dirt. They are smaller than other wolf species, their ears rounder — it could be easy, to the untrained eye, to confuse them with coyotes.

SOUTHEAST ARIZONA — Inside a large chain-link cage at the Southwest Wildlife Conservation Center, a Mexican gray wolf gently moves from behind a tree and into the open air. It stands in the midday sun, dark-lined eyes looking intently beyond the fence, before settling under the tree for shade.

This is one of 16 wolves at the north Scottsdale center, part of the Mexican Wolf Species Survival Plan. The wolves in the enclosure are shy, dusty gray and brown coats disguising them against the dirt. They are smaller than other wolf species, their ears rounder — it could be easy, to the untrained eye, to confuse them with coyotes.

A battle over this endangered animal has surfaced in southeastern Arizona, where those concerned for livestock are pushing back against recent expansion of the wolf’s habitat. In Cochise County, officials are spending thousands to reverse this expansion, though no wolves roam the region now — and it’s unclear whether they ever will.

“When you’re talking about Cochise County opposing, it’s all prospective,” said Michael Robinson, a Mexican wolf expert at the Center for Biological Diversity, an organization that advocates for endangered species. “This fear that wolves are going to establish in Cochise County — well, maybe they will in five years, but right now the population is going down. It’s shrinking. And it’s less and less likely.”

The ranching lobby isn’t the only challenge. The wolf’s wild population rose steadily for the past few years, peaking at 110 wolves by the end of 2014, but that number fell to 97 in this year’s census. Two wolves died during the annual wolf count after they were tranquilized.

The survival or demise of the Mexican wolf has long taken an emotional toll on both sides of the border, and Cochise County is now a key part of an enduring debate.

The troubled history is exemplified by a conversation the center’s director and founder, Linda Searles, had with a rancher.

“He said, ‘It took us 100 years to get rid of the damn things, and now you want to bring it back,’” she said.

Cochise County: A No Wolf Zone

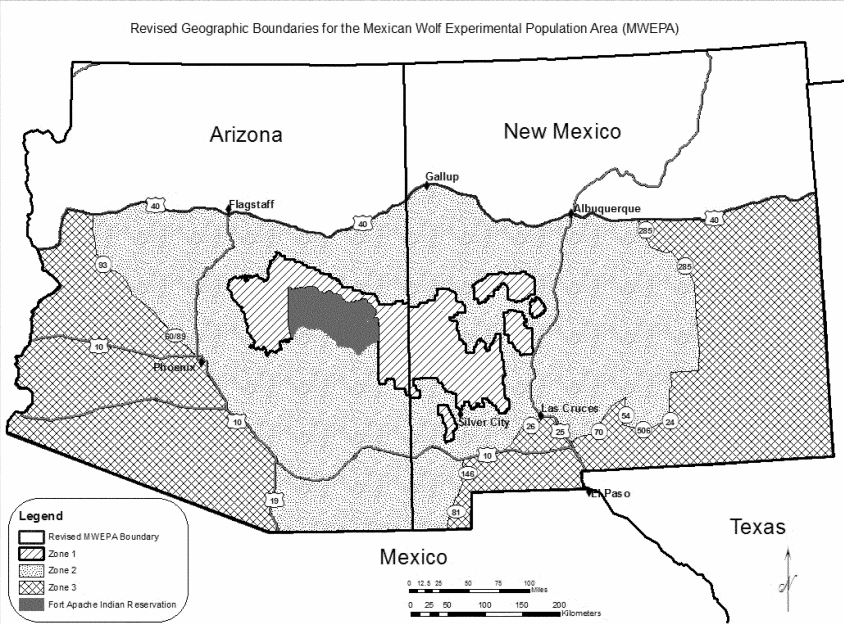

The wolf, whose U.S. population is in east-central Arizona and west-central New Mexico, was given space to roam more widely under a new rule announced in January 2015 by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that expanded their territory south of Interstate 10, into southeastern Arizona.

Cochise County is pushing some of the strongest efforts against this expansion of the Mexican gray wolf experimental population area, where wolves released from captivity are allowed to live.

There are no wolves in Cochise County now. But that hasn’t stopped the county from spending tens of thousands of dollars on an effort to fight the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s rule.

Many of the arguments come down to sharing space. Board Chairman Richard Searle believes that introducing wolves into the region will put stress on ranchers and their livestock.

The wolf’s diet consists 80 percent of elk, of which there are few in Cochise County, said Sherry Barrett, the Mexican wolf recovery coordinator for U.S. Fish and Wildlife. The other 20 percent includes animals such as deer, rabbits and possibly livestock.

“Without a prey base, it’s not only unfair to our residents who have domestic livestock and pets and whatnot, but it’s also unfair to the wolf,” said Searle, who’s been on the county’s Board of Supervisors for 12 years.

In mid-March, the Sierra Vista Herald reported that the county allocated more than $64,000 toward natural-resource issues. One of those concerned the wolf’s expanded range.

The county has paid about $36,000 toward a lawsuit filed by the coalition of Arizona and New Mexico counties against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Cochise County joined the lawsuit after the wolf’s territory was expanded, the Herald wrote. The lawsuit also includes private organizations, such as the Southern Arizona Cattlemen’s Protective Association.

The litigation, which has no initial hearing date according to Barrett, argues against the experimental zone’s expansion as well as a “restrictive” rule that, among other things, requires ranchers who “take” a wolf — which includes harming, shooting or killing it — to report it within 24 hours.

More than $24,000 of the $36,000 was spent to hire a consulting firm, which produced a 189-page document that became the foundation of the county’s arguments.

Cochise County Supervisor Ann English has mixed feelings about the county’s involvement in the lawsuit.

“My husband and I raise cattle and I see the wolf as a predator for cattle when they do not have the choice of elk or deer as food,” English said in an email interview.

“My concern with the issue of litigation on the wolf issue is money,” she continued. “How much should the county spend on research to fight the lawsuit (sic)?”

The county set a limit of $50,000 for the wolf issue, English said, but mounting costs — including payment for the consultant and attorney involved with the litigation — has brought those costs close to $100,000.

“Spending too much is relative to benefit gained and I feel we are close to the limit I wish to spend of tax dollars,” she wrote.

In Bisbee, the only wolves are pets

On the patio of the Copper Queen Hotel in “Old Bisbee,” Terry Wolf and her band stand ready to play in front of an audience of bikers and beer bottles. Smiling and facing an old-fashioned microphone, she strums her acoustic guitar, gently swaying through covers of country classics.

Wolf, 63 a popular musician in the city, was the first inductee to the Bisbee Music Hall of Fame. She has also bred and raised wolf-dog hybrids in the region for 35 years (this is where her stage surname comes from).

Wolf raises her wolf dogs on a 20-acre property along the Mule Mountains near Bisbee. She says nearby ranchers “can’t stand” her animals, mentioning times when her own wolf dogs were poisoned.

“I mean, it’s an age-old problem,” she said during her break inside the Copper Queen Hotel saloon, taking occasional sips from her drink. “Ranchers and wolves.”

The wolf dogs prove to be a source of confusion for people who think they are Mexican wolves released by U.S. Fish and Wildlife. Barrett said that a couple of times a month, the agency gets calls from people claiming to see Mexican gray wolves in Cochise County, when really what they saw were wolf dogs.

Wolf said she supports the reintroduction of wolves toward the U.S.-Mexico border and disagrees with Cochise County’s litigation efforts. She noted the positive changes wolves have brought to ecosystem diversity in other regions of the United States.

Bill Stoller, a 26-year-old Bisbee resident, purchased two wolf dogs — Loki and Tequila — from Wolf. Like her, Stoller is a musician who also supports the expanded experimental population zone for the Mexican wolf.

“I think it’s a good thing,” Stoller said. “Ranchers don’t like it so much. They’re business people, and I can understand that, but I also don’t have that much sympathy when it’s about money.”

Wolf, who got her first wolf dog 40 years ago, cites the strength of the ranching lobby as the reason why Cochise County continues to participate in the litigation so strongly.

“I don’t really see the wolves as being any kind of huge threat to ranching around here,” Wolf said. “But I’m not a rancher, and I’m a vegetarian.”

The conflicting interests of the area — its economic value in the livestock industry and its historic role as the wolf’s native range — will remain at odds until all sides can understand each other, said Searles, the conservation center director.

“It always comes down to human-wildlife conflict,” Searles said. “You don’t want the ranchers to go out of business, but you want the wolves to be there so we can all live together, because the wolves were here long before us.”

Both advocates, opponents against the feds

The Mexican wolf is the smallest and rarest subspecies of gray wolf. Over a century ago, the heart of its territory was the Sierra Madre mountain range in Mexico, spanning upward into the southwestern United States.

In 1915, to protect livestock and ranchland, the United States government began to contribute to what ranchers were already using to eliminate the wolf, from trapping to shooting to poisoning.

The species was listed as endangered in 1976, and in 1982, Fish and Wildlife passed an interim recovery plan. That plan was left incomplete because the wolf was so critically endangered — only seven wolves remained from which to recover the population.

Since then, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has made multiple efforts to develop a full recovery plan, composing recovery teams whose meetings have been canceled and drafting plans that never got finalized, Robinson said. Fish and Wildlife expects to have a plan completed by the end of 2017, Barrett said.

Lawsuits against the service from the Center for Biological Diversity as well as the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Attorney General’s Office both focus on Fish and Wildlife’s failure to develop a full recovery plan with the most recent science.

The lack of a recovery plan also crops up in the lawsuit Cochise County is taking part in, which states that the January 2015 rule is proceeding “without any regard to recovery and without regard to any informed population objective … and without regard for the lives and property of those who will suffer as a result of its hasty actions.”

No matter the argument, on all sides of the debate, emotions run high. And they have throughout history.

“Actions taken against a predator that causes loss of dollars and food and that competes with man for wild prey inevitably take on the emotional overtones of a crusade,” the 1982 recovery plan states. “Any recovery effort must still deal with the residues of that emotion.”

Ensuring the wolf’s survival

While Cochise County continues to spend money on litigation against the rule expanding the Mexican wolf’s experimental population area, no wolves are in the area now, and they’re not likely to move that way soon, Robinson from the Center for Biological Diversity said.

If the wolf population does expand, U.S. Fish and Wildlife expects it to head westward across the Mogollon Rim, where there are more elk, Barrett said.

Some think the population should be focused outside the United States entirely. Searle, along with Gov. Doug Ducey, believes most of the recovery efforts should take place in Mexico, where the majority of the wolf population originally lived.

But Mexico and the United States partner in their handling of the wolf reintroduction. Barrett and other Fish and Wildlife employees were in Mexico City earlier this month to discuss habitat mapping for the wolf.

Like the United States, Mexico has its own rules to deal with endangered species such as the Mexican wolf. The “constant collaboration between both nations” is necessary to ensure the species’ survival, according to researchers with Mexico City’s director of zoos and wildlife.

“That is to say, Mexico and the United States possess the same responsibilities,” they wrote in an emailed statement. Southern Arizona is good habitat for the wolf, they added. According to the statement, only three wolves have been confirmed living in the wild in Mexico.

Opponents in the U.S. still fear wolves will eventually make their way into Cochise County.

“Ultimately, if this is done, they will be here sooner or later,” said Searle, the county chair.

Given the recent drop in the counted population of Mexican wolves in the United States — from 110 to 97 — it’s unlikely they’ll be venturing outside of where they already live, Robinson said.

“What happens when instead of going from five wolves to eight wolves, you go from five wolves to three wolves?” Robinson said. “You obviously have less of a density-dependent impetus to disperse. And that’s what we saw last year.”

One speculated reason for the population decline is a lack of genetic diversity. The current wild population’s genetic diversity is low because the group’s genes come from just one segment of the already small group used to restore the population decades ago.

In order to survive, then, the wild population needs the introduction of new wolves from the captive population to increase its diversity, Robinson said.

Allowing Mexican wolves to roam in places like Cochise County is part of the strategy for their conservation, Robinson said. Today, it isn’t a serious expectation for the future.

source

No comments:

Post a Comment